Miners Take off for The Great – and More Profitable – North

Bitcoin (BTC) miners across Europe are fleeing to the northern parts of Norway and Sweden to cut power costs as energy prices skyrocket on the continent and bitcoin flatlines.

Mining economics has stopped making sense on much of the continent. Natural gas prices reached a record high of 321 euros ($309) per megawatt-hour (mWh) in August, compared with 27 euros a year ago. Meanwhile, the price of bitcoin has lost about 60% of its value this year and is hovering around $20,000.

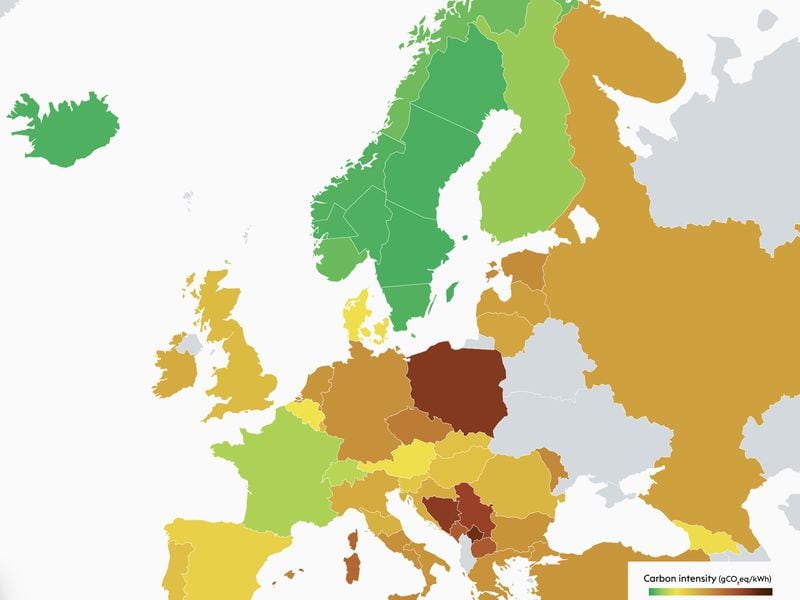

Energy in the northernmost parts of Norway and Sweden is as much as 10 times cheaper than in the southern parts of those countries. That’s because the countries are split into different energy markets. The Nordics have a higher proportion of electricity coming from renewable energy compared with the rest of Europe – almost 100%. But the southern parts of the countries are connected to European markets, which means higher demand and thus higher prices.

Back in March, when CoinDesk visited Kryptovault in southern Norway, CEO Kjetil Pettersen said that his company, which runs data centers that host large-scale bitcoin miners, was looking to expand in the north as energy prices were starting to rise. That was before Russia invaded Ukraine, sending natural gas prices soaring. The company closed its operations in the south in May and June and has been slowly moving its machines to a site in the Lofoten region, just north of the Arctic Circle, Pettersen told CoinDesk.

Similarly, a smaller bitcoin mining site in southern Spain that CoinDesk also visited earlier this year is being moved to Paraguay, said the owner Jon Arregi.

The companies' situation is emblematic of how the bitcoin mining industry in Europe has been responding to energy prices that have shot up this year, largely because of the war in Ukraine. Miners are either shutting down or moving to places where energy is cheaper, especially in the far northern reaches of Norway and Sweden where there is abundant cheap hydropower, or in the Americas, even as they fear tougher regulations may be coming in states like New York.

Daniel Jogg, CEO of Hungarian miner and equipment supplier Enerhash, said that many companies in Germany have also stopped their operations there and are looking to move to the U.S. or Sweden.

Fiorenzo Manganiello, founder of Switzerland-based Cowa Energy, a mining company that also provides venture funding, said that in southern Norway “it’s impossible” to mine given the high energy prices. The current macroeconomic situation has been a “disaster” for the mining industry in Europe, he said.

But while the Nordics’ fragmented energy markets can bring opportunities, they also present difficulties in hedging power prices, Jogg said. The financial products sold to companies looking to hedge their power costs are aimed at the entire Nordics market, but the actual price of power miners are looking to hedge is likely for a narrower region, where they mine, he explained.

Power costs a pretty penny in much of Europe. In the second quarter, the average wholesale price of energy in France and Germany was more than double what it is in the U.S., according to the International Energy Agency. In mid-September, following measures to curb the price hikes, the wholesale price of power in many European countries was still more than 350 euros ($350) per megawatt-hour, several times more than what miners are looking for to break even.

Bad timing

The timing has been bad for miners, and several factors have contributed to an ever-worsening energy crisis. The war in Ukraine increased the price of natural gas after European political leaders sanctioned Russia, one of the continent’s biggest suppliers of fossil fuels.

Also, over the last few years European countries have decommissioned nuclear plants and closed coal factories, which also limited the supply of power. France, which has the largest share of its electricity generated by nuclear power in the world, shut down 32 of 56 reactors for maintenance this year.

The energy crisis has caused Germany to backtrack on some measures in a surprising move; the country’s parliaments voted to bring coal plants back to life over the summer.

Meanwhile, as the war in Ukraine rages on, European Union leaders have placed more sanctions on Russian gas companies, which prompted Russia to close the Nord Stream 1 pipeline in early September. That pipeline, which transports liquified natural gas from Russia to Germany, was allegedly “sabotaged” along with Nord Stream 2, on Sept. 28.

However, moving to the northern parts of Scandinavia isn’t risk-free for miners. There were a few days in September when the price of energy in northern Sweden increased to around 20 euro cents per kilowatt hour (kWh), compared with an average of around 3.5 euro cents per kWh the rest of the year, because of low wind production, Jogg said.

The future of the energy market looks uncertain, with demand expected to increase in the next few months as households try to cope with winter temperatures while European leaders remain unwilling to back down on sanctions.

At the same time, Europe has managed to fill its storage piles with natural gas that could help the bloc make through the winter. The initial shock from the Nord Stream pipeline closure to the energy market appears to be subsiding, with prices coming back down in the past few days.

New developments in nuclear power may also relieve some pressures. Rusinovich noted that a nuclear power plant set to go into full operation in Finland later in the year, the country’s fifth, and reactors in France coming back online in early 2023 after maintenance, could free up some of the market pressure on Norway and Sweden.

Policy implications

Europe’s politicians have started calling on their people in their countries to reduce their energy consumption – or else. French President Emmanuel Macron, for example, said that plans to ration energy are being prepared "in case" they are necessary.

In a speech earlier in September, European Commission President Ursula von der Layen said the commission is looking to overhaul the energy sector by imposing a cap on energy companies’ profits and perhaps a cap on the price of natural gas. The Commission is the European Union’s executive body.

Yet, Manganiello of Cowa Energy doesn’t see EU-level policy on mining coming any time soon because that process typically takes a long time, and it is usually local municipalities that approve mining projects.

But in the current crises in energy, geopolitics and possibly domestic affairs, “there is a lot of, let's say, witch hunting” and mining in the past has always been “an easy target,” Rusinovich said.

In the meantime, the icy pastures of northern Norway and Sweden beckon.