Amid Market Rout, Crypto Miners Are Still Building

Throughout the summer, CoinDesk traveled to two U.S. states to visit bitcoin (BTC) mines to see how, even in the midst of a crypto winter, miners are still building data centers to power the Bitcoin network.

Bitcoin miners have had a tough few months as the price of the world’s largest cryptocurrency has dropped precipitously. With low bitcoin prices, miners’ revenues have diminished, and some have been forced to sell their mined tokens, machines and even facilities for cash to run their operations.

On top of that, the Biden administration on Sept. 8 dropped a report calling for industry standards to limit cryptocurrencies’ environmental footprint. Should these fail, authorities and legislators in the U.S. should consider measures to limit or eliminate energy-intensive proof-of-work algorithms that bitcoin miners use to drive the Bitcoin network, the report recommended.

Still, bitcoin miners are busy building out more capacity. Visiting these sites shows how the industry in the U.S. is continuously iterating. Mining data centers come in many shapes and sizes, depending on the location and available energy supply. Miners have been at the forefront of trying various innovative permutations of data centers, such as immersion cooling, that are used for other purposes, too.

These buildouts have borne fruit for the network, with computing power steadily growing over the past few months.

Merkle Standard and Bitmain facility in Washington

Near Washington state’s border with Idaho lies a 120-year-old paper mill that has been closed since the start of COVID-19. It is situated close to a river and has its own water treatment facilities, but little other than homes is around its remote location. It’s just about the last place where you’d expect to find a bitcoin mine testing some of the world’s most innovative mining rigs, but there it is.

The facility is a co-venture between private bitcoin miner Merkle Standard and Bitmain, the world’s largest manufacturer of bitcoin mining rigs. The site is currently capped at operating at 100 megawatts (MW), about the annual capacity of 10 homes in the U.S., and has the electrical infrastructure to reach 225 MW, Merkle Standard Chief Operating Officer Monty Stahl told CoinDesk during a site visit.

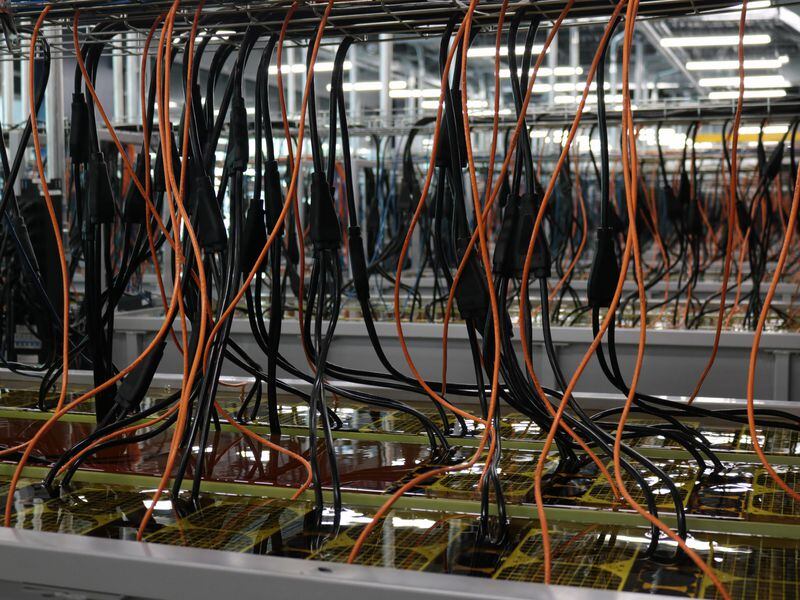

The water treatment facility is no miscellaneous accessory. The site is a testing ground for Bitmain’s S19 XP Hydro, a mining machine that cools itself using water pipes that run near the processor chips.

In order to run these machines, “you need to understand and respect water chemistry,” Stahl said. Operating these pricey rigs with the right type of water is key to their longevity and efficiency, he added.

“In my opinion, this is superior technology and more scalable than immersion,” because the chips aren’t sunk into chemical blends, said Stahl.

The site manager also takes pride in the blue collar talent that he inherited from the mill. He is often amazed looking at how the people that run the water treatment plant do things, he said.

Most of the mining, however, takes place outside of the paper mill, in Bitmain’s Antbox mining containers. These are shipping containers that have been repurposed to hosting mining machines. Merkle Standard has preserved the paper mill and plans to reopen it. About 150 people were employed there, he notes.

Walking through the cavernous halls of the paper mill, steps echoing, feels like something out of a horror movie. Time stopped when the paper mill closed due to bankruptcy in 2020, but it never started again. A few details in the space are stark reminders of the people who are no longer there: a microscope standing upright at the lab ready to be used, a plaque commemorating the one-millionth ton of newsprint produced in 1994, a board noting the longest-serving employees.

“It’s humbling to work here every day” and to be reminded of what this place had meant for generations of people that worked there, said Stahl.

CleanSpark, Atlanta Area, Georgia

CleanSpark (CLSK) was founded in the late 1980s as a software company, only to meander from one business to another; in the middle of the last decade, it was an alternative energy company. Its evolution as a bitcoin miner is apparent across two sites in Georgia.

At College Park, near Atlanta’s Hartsfield airport – the world’s biggest by passenger traffic – is a 47 MW bitcoin mine divided into four parts.

The site was originally a traditional data center with about 50 clients, which have slowly been leaving the building. About six are left, including the city of College Park. Once they are gone, the building will be retrofitted with immersion-cooled bitcoin miners, said Zach Bradford, CEO of CleanSpark. The building uses what looks like air-conditioning equipment to cool down the machines; cold air is pumped through vents placed in front of the racks where the mining rigs sit.

Just next door is another bitcoin mine that uses evaporation cooling. One of the walls of this building is a kind of perforated wet wall the air goes through before coming into the building, its temperature dropping as it goes through the water, which in turn evaporates. On another wall are fans to pull the air into the room. When water evaporates from a surface, the surface’s temperature drops, much like when sweating during a run. The company says it plans on eventually retiring this system for another type of evaporative cooling.

A few mining containers made by Bitmain and called AntBoxes sit outside the building, which work similarly to the evaporation cooling building; their back walls are fitted with streaks of a cardboard-like material where the steam comes through.

The final part of the College Park facility of which the CleanSpark team is proudest is a set of air-cooled containers running outside a building the company has designed, laid up in two stories. This is the loudest part of the facility, which is why the company built a sound-diminishing wall and planted trees around this building.

The temperature changes every few seconds as one walks through what the company calls “Clean Block.” Hot air comes out of one side of the containers and cool air comes into the other. It’s like walking through a supermarket with an open freezer door in one aisle and a hot lamp heating food immediately in the next.

About 40 minutes away, in Norcross, is CleanSpark’s newer facility. Using “immersion cooling,” the mining rigs, with their fans removed, are immersed in a mineral oil in big tanks. As the liquid heats up from the heat of the machines, it rises and spills over and is directed into a cooling system.

Instead of loud fans, “it’s like being in a spa,” remarked Matthew Schultz. He wasn’t wrong. The sound of the mineral oil flowing does sound like a relatively quiet indoor fountain.

Bitfarms, Moses Lake, Washington

“That’s an old semiconductor plant,” said Jayden Perry excitedly. The manager of the Bitfarms (BITF) sites in Moses Lake, Washington, was pointing to what looked like a steel and concrete giant sleeping in a golden wheat field, right by one of the Bitfarms facilities. The friendly regional manager admitted that he likes learning about now-abandoned industrial facilities in Washington’s agricultural heartland.

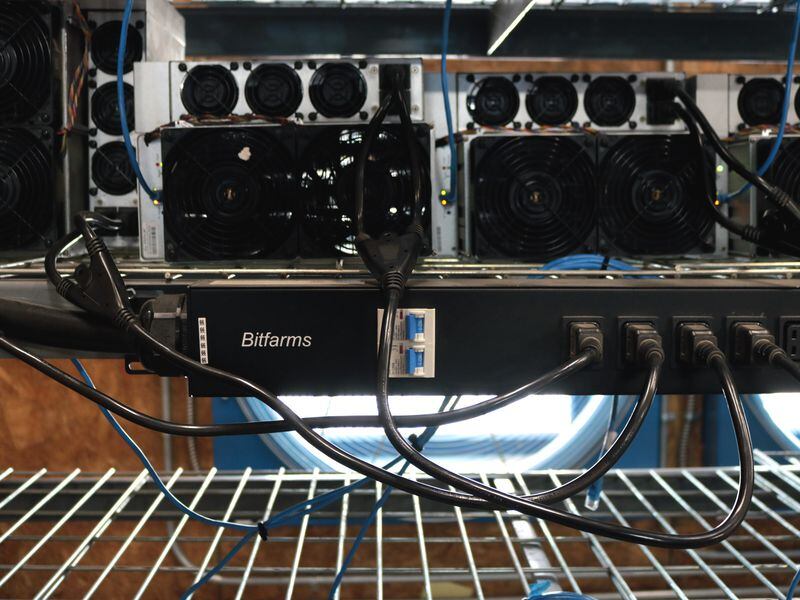

The Canadian mining company bought two sites in November 2021 from an undisclosed party and is working to revamp them to Bitfarms’ standards. The sites are all air-cooled, meaning they use the outside air and sets of fans to keep the temperature low, as temperatures most of the year are cool in this part of the country. One part of the revamp project is to change and organize the cabling of the racks so that the machines aren’t buried behind a web of dusty cables. Another is to install Antminer S19J Pro miners.

The two sites, which total 20 MW and around 6,100 machines, run on hydropower supplied by the Grand Coulee dam, the biggest in the U.S. by power produced.

The Bitfarms facilities aren’t the most exciting or innovative of the bunch, but they are nonetheless part of the network of computers that keeps bitcoin going. The sites are also indicative of a trend that has just started amid the crypto winter: consolidation. Smaller operators are increasingly struggling to break even and are forced to liquidate their facilities, opening up the market to well-capitalized firms looking to buy new sites. The mining firm is also expanding across four countries – the other three being Canada, Paraguay, and Argentina – in order to shield itself from geographic risks.

Read more: Bear Market Could See Some Crypto Miners Turning to M&A for Survival

The bitcoin mines on our latest trip show something that is often forgotten: While supporting a decentralized infrastructure revolutionizing finance, these facilities are just huge, noisy data centers that consume a lot of power.

Miners are essentially working on data center design, and the technology going into these facilities, like cooling, wiring and managing the machines, could all be used in data centers beyond crypto.

As much as the Bitcoin network is in many senses designed to consume a lot of energy, mining firms have a built-in incentive to keep their costs low – or risk falling behind a very competitive market. This pushes them to try out different ways to build and operate data centers; from mining at the edges of the world, like Siberia, to plunging millions of dollars of equipment into mineral oil to keep them cool.

Some miners, like Hive Blockchain and Hut 8, which were not included in this story, are already trying to diversify into other data centers like those processing artificial intelligence and cloud computing.

Perhaps in just a few years, your Google Maps directions or your Yelp reviews could be processed in a data center that was inspired by bitcoin mines.

Read more: Large Ethereum Miners Look to Cloud Computing, AI Ahead of The Merge